Data Portraits: Exploring Privacy and Design

Ethical considerations in personal data digital landscape

-

Client:

Master Digital Design

- Team:

- Disciplines:

-

Schoolyear:

2025-2026

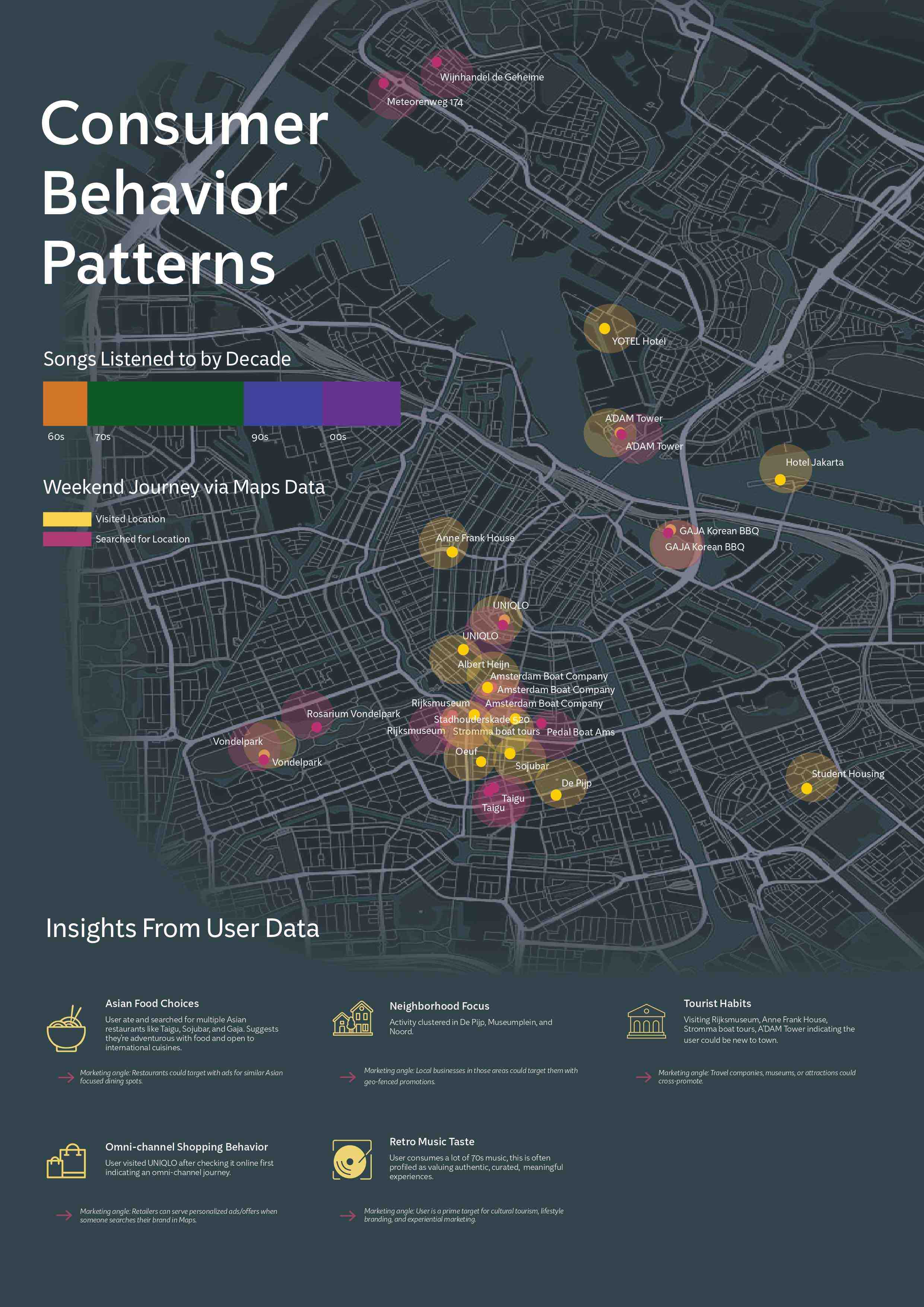

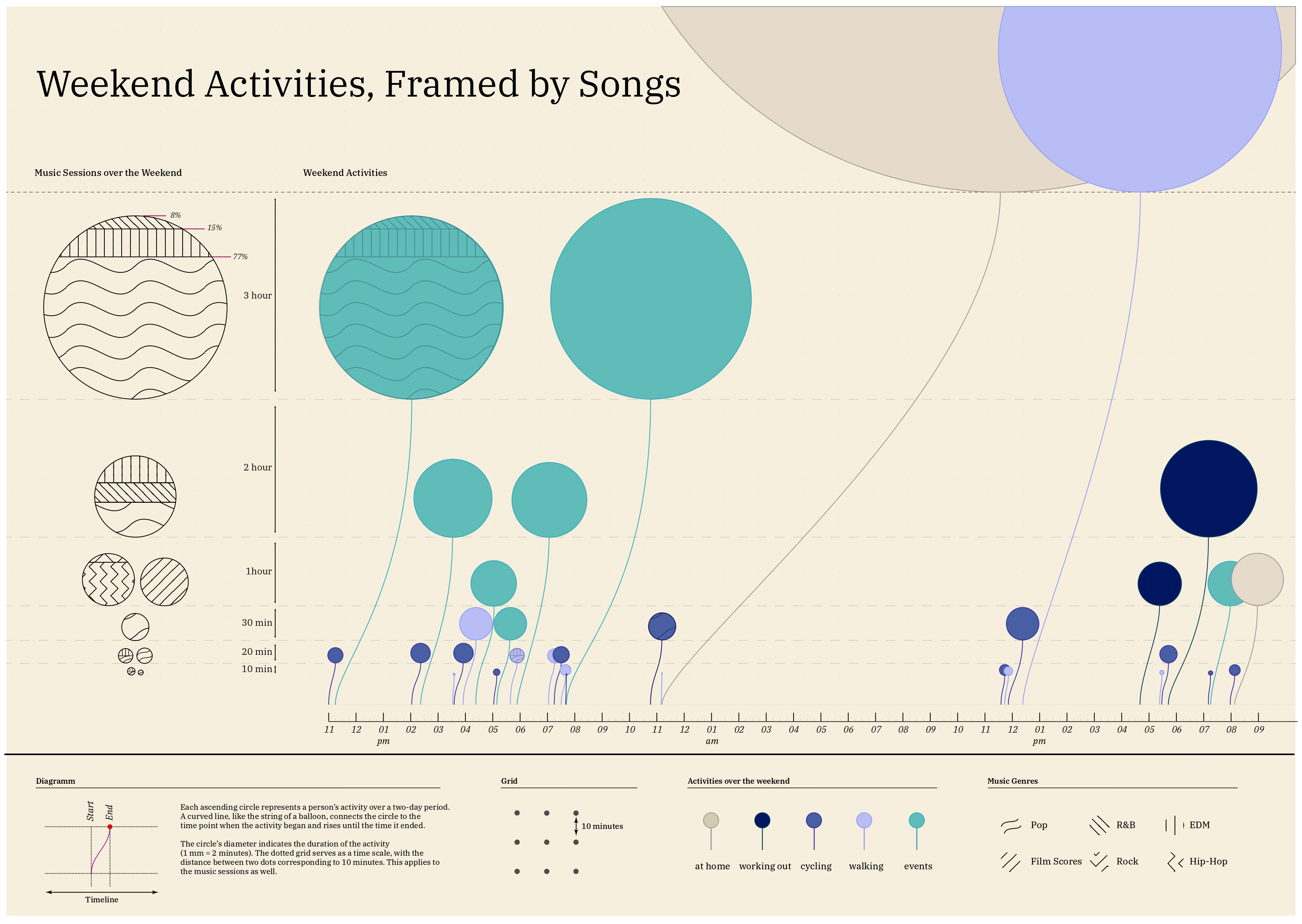

Our first sprint of the year challenged students of the learning track Interaction Design to create ‘data portraits’ — visualisations based on anonymised data shared by their peers. The project was more than just a creative exercise: it sparked insightful reflections on data privacy and designers' ethical responsibilities in today’s digital landscape.

It also helped students to deepen their appreciation of personal data's value, vulnerability, and the complexities of designing with privacy in mind.

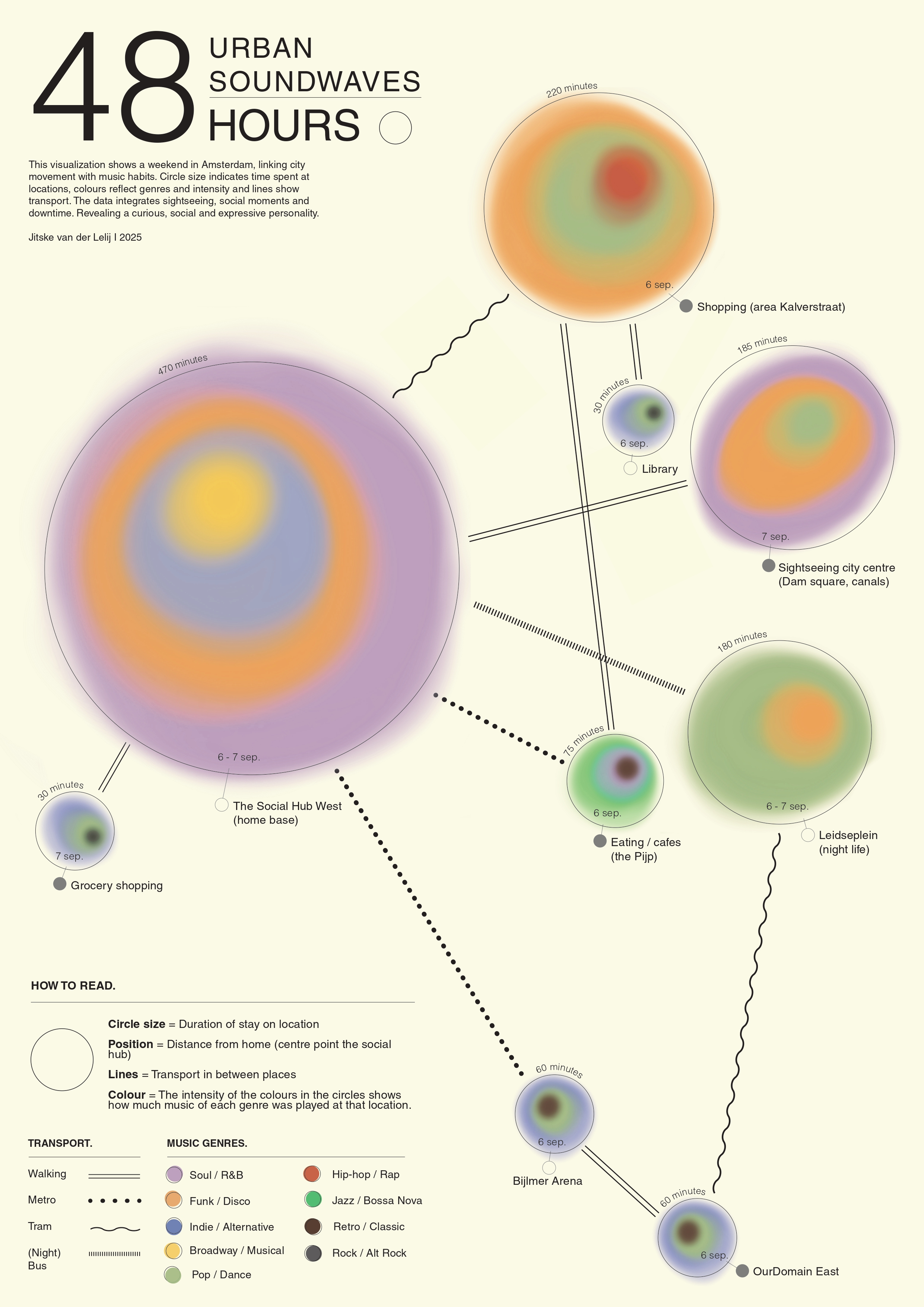

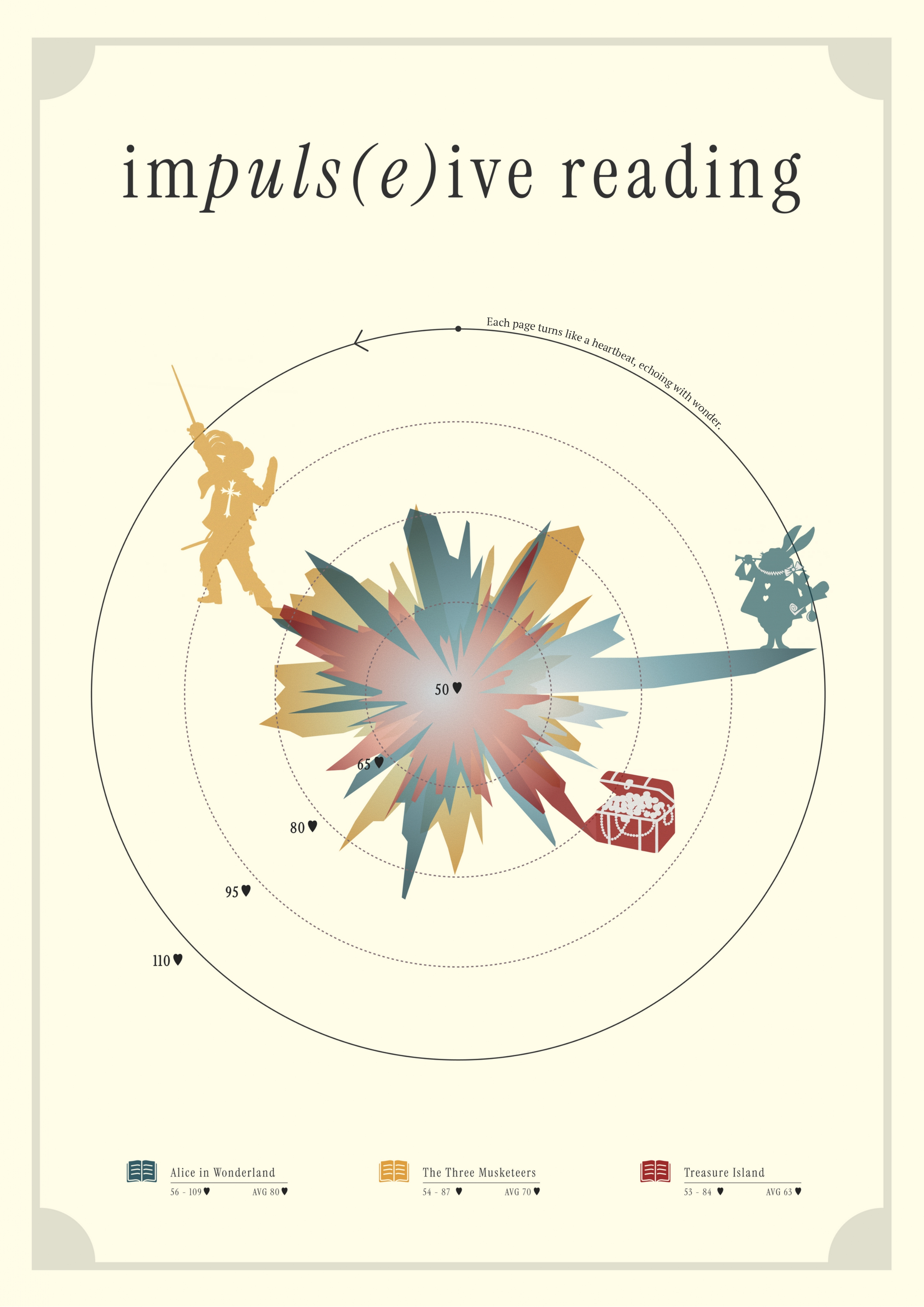

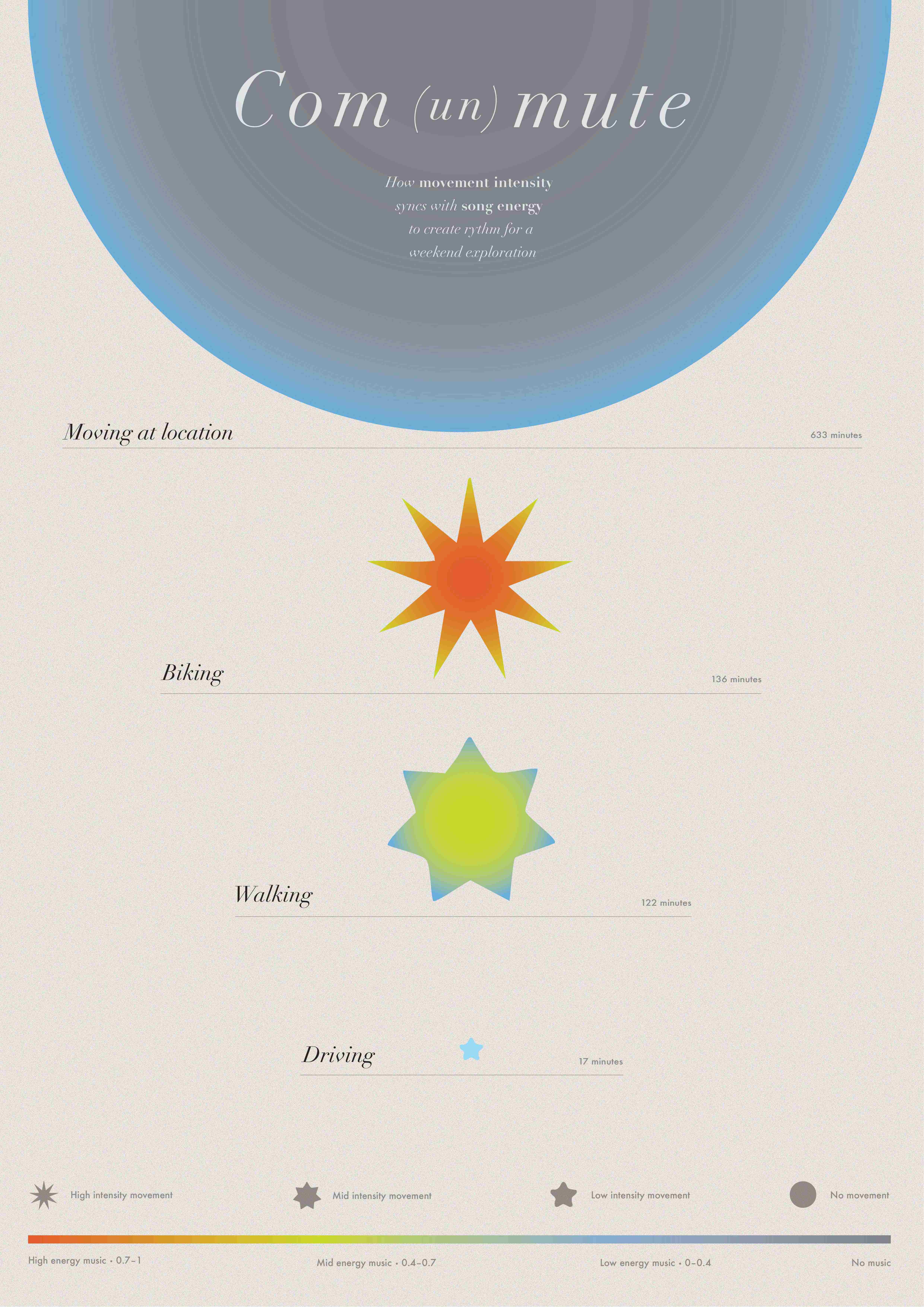

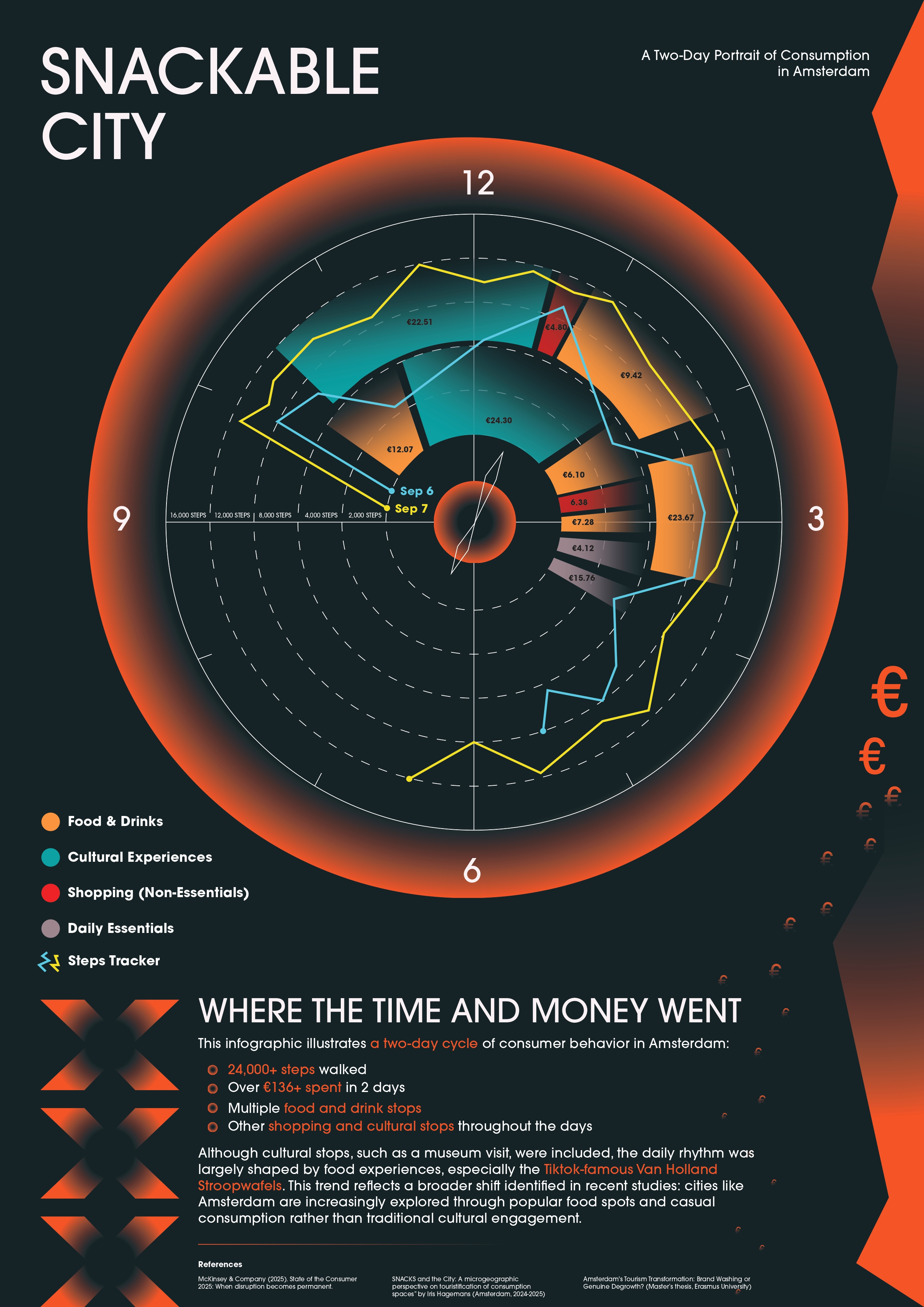

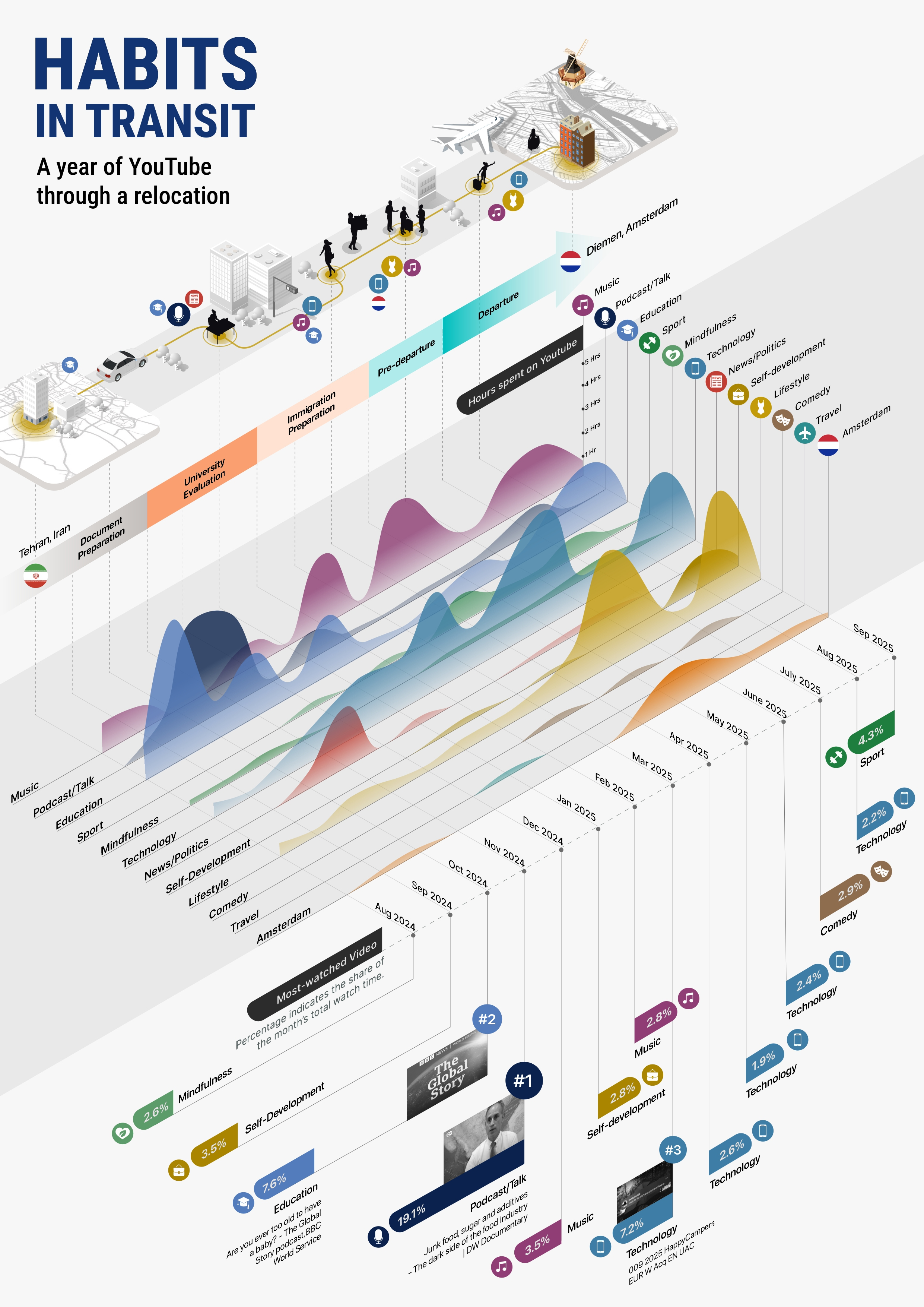

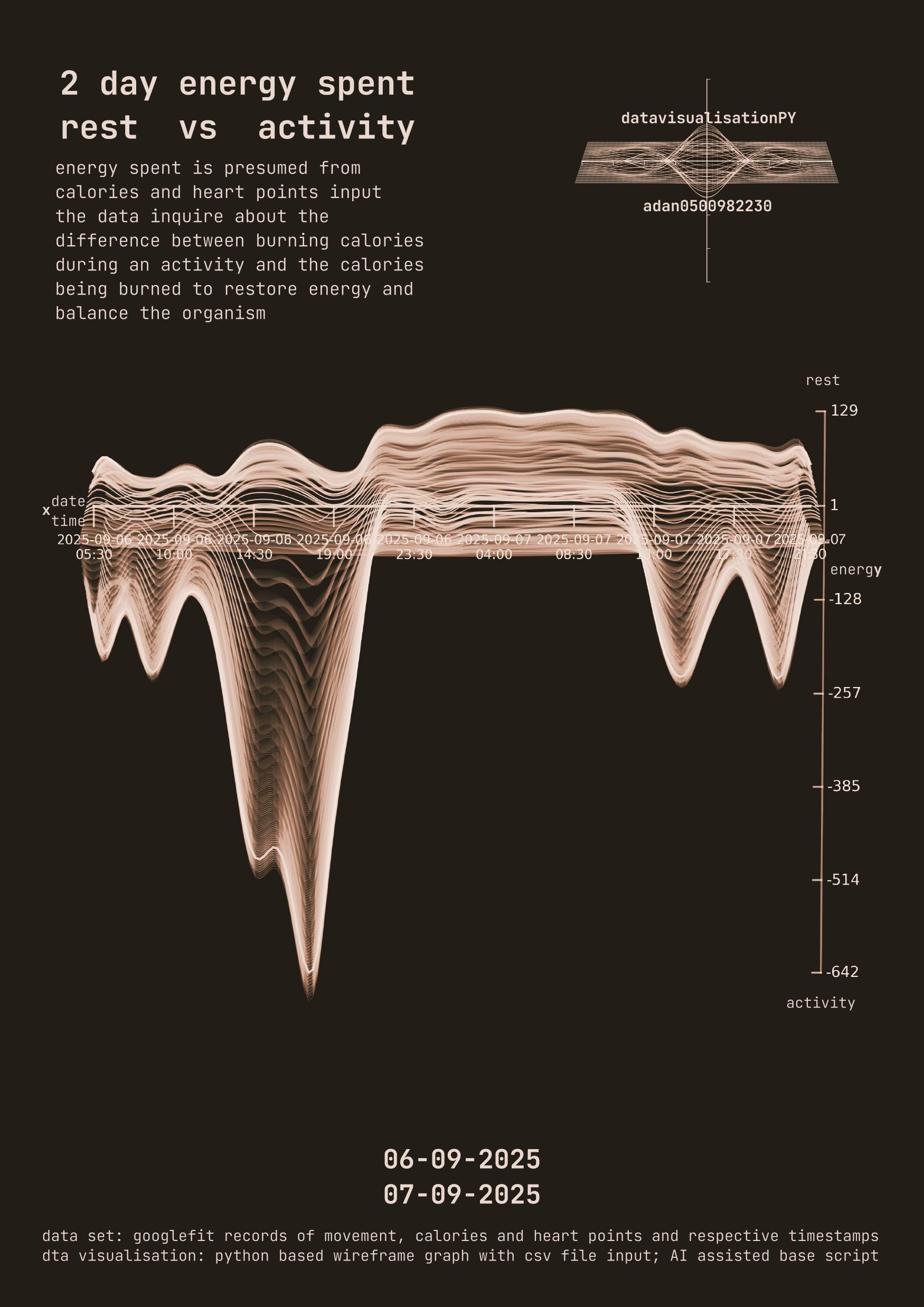

Using personal datasets such as Google Maps locations, Spotify playlists, and Apple Health metrics, students translated numbers into visual stories (data portraits) revealing aspects of identity and routine while protecting anonymity. The exercise helped students realise just how much can be revealed from small fragments of data, and how easily assumptions can shape the story that gets told.

Throughout the process, several questions surfaced:

- Who owns personal data, and is it ever truly anonymous?

- What responsibilities do designers have in curating, visualising, and interpreting personal data?

- Where is the balance between convenience, personalisation, and privacy, especially when societal habits and technology evolve rapidly?

- How do designers avoid making unwarranted assumptions when translating data into visual narratives of identity?

Insights Extracted from Student Reflections

After concluding their data portraits, students were invited to share their reflections on the exercise and their findings. Here are some of the main points.

The Ambiguity and Emotional Complexity of Data Privacy

Many students expressed unease and surprise at the intimate information datasets could reveal, even when anonymised.

Damian Westerborg noted, “Although the assignment left me feeling quite tense, it raised a great question: ‘What are the responsibilities of designers in the context of data privacy?’”

Emily Sonnier described her discomfort: “Looking at my music and podcast taste on Spotify, I didn’t want others to judge my music taste. It really put into perspective how much companies know about us without our knowledge”.

Parichehr Talebzadeh noted that the design process exposed vulnerabilities: “Tiny partial data (a timestamp here, a location marker there) can convey ... intimate related details about a person, such as their possible age, location, and even daily habits.”

(continue reading after the portraits below)

Ethical Design: Reflection and Duty

Designers’ choices shape others’ identities, sometimes based on assumptions or incomplete context.

As Matilde Cantinho Estevinha wrote, “I realised how much I was filling gaps with assumptions. Assumptions are powerful for storytelling, but quite prone to misinterpretation, or worse: misuse.”

The need for ethical boundaries emerged repeatedly: “Designers in particular need to define clear boundaries between data used for connection and data that must remain private.”

Karim Youssef asked, “Who owns the data, the individual or the platform? Is it ethical to visualise someone's intimate movements and spending habits without their consent?” (note: students did share their data with their consent).

(continue reading after the portraits below)

The Balancing Act: Convenience vs. Privacy

Many students recognised the social tension between convenience and privacy. Watis Kotitrakool wrote, “We pay for speed and ease with our data. We also like to think we control what we share, yet big companies gather far more than we notice. Much of it is collected quietly, in the background.”

The assignment prompted students to envision the designer’s role as both a creator and a steward: “Our role is more than visualising data beautifully, but also to question whether and how it should be visualised at all. By respecting privacy, embracing ambiguity, and acknowledging bias,” says Matilde.

(continue reading after the portraits below)

Changing Perspectives and Agency

Several reflections described a transformation in mindset:

Daniël Bolt admitted: “My perspective has been changed. ... Companies know more about you than you know about yourself.”

Lisa Schneider: “This experience pushed me toward a more nuanced perspective: we urgently need ethical data practices and strong protections, especially as everything becomes digital.”

Mariana Bozano: “The project made visible how data can be misused, underscoring a personal and professional responsibility to advocate for privacy and challenge exploitative practices.”

What about now?

The data portrait sprint provided a compelling environment for students to grapple with the value, risks, and responsibilities of personal data in design. The assignment exposed both discomfort and curiosity, raising deep ethical questions and underscoring the need for critical engagement.

By reflecting on their own assumptions and biases, students gained new agency and appreciation for the responsibilities they will hold as designers, committed not just to creativity, but to privacy, ethics, and responsible innovation in a rapidly shifting digital world.