The Useless Machine Chapter 2: Reconnaissance

Those following the adventures of the Useless Machine project will know of our quest against utilitarianism: design often takes a formulated approach and steps away from its artistic roots. We decided to form a small rebellion against the powers at be, yet, after writing our last post the three of us suddenly felt very lost.

There were so many directions to explore and pools of information to dive into, we needed to understand the essence of what we were doing. So, we took a step back to view our thoughts at a distance and remember why we started this project in the first place. We regrouped in the meeting room and mapped the bits of data from within our brain on to the large whiteboards.

Us three stooges have been driven by the idea of the value of instilling life into an artefact, and are fascinated by our species’ ability to form emotional bonds with emotionless objects. What urges us to connect to our surroundings so much - even when it’s about lifeless things? We wondered if, by replicating this attachment within objects that we created, it would result in a form of value for the user.

You do not simply throw your grandparent away for being less physically functional as they previously were.

Mission: Activate Emotional Controls

Take, for example, your smart device: on good days, it simply works. The majority of us do not know how, nor does it concern us. It works in the background as we go about our day-to-day lives, quietly working its magic. That is, up until something unexpected happens and the device fails, resulting in a frustrated and annoyed user. Despite our strong bond, we discard of our dear objects with a disturbing ease once they stop serving us. You do not simply throw your grandparent away for being less physically functional as they previously were (or at least we hope you don’t…). You love them despite their flaws. Yet, with our objects, we lose a sense of understanding and, in the process, empathy.

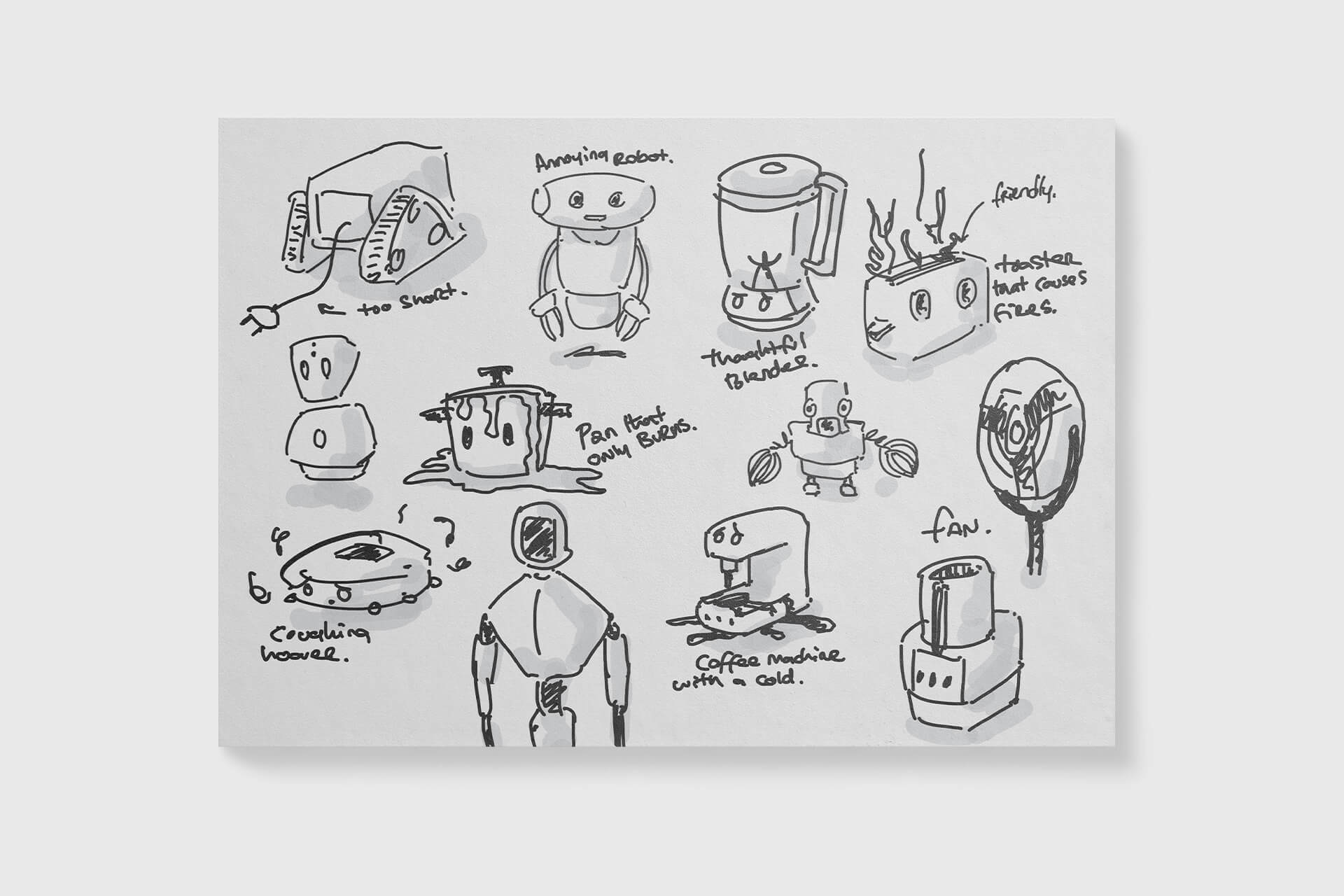

Now imagine if instead of making you a nice warm cup of coffee, your barista machine would spit, drizzle and spurt the brown, caffeine based liquid everywhere but in your cup. Stressful, right? But what if it apologizes sincerely afterwards? How would you feel and how would your relationship with that object change? Here lies the essence of our quest, the search to find emotional worth in objects and devices that have no perceived functionality.

We realised that an artefact that fails to complete its task is deemed worthless. However, when said artefact struggles and its trying nature becomes visible, we feel a sense of empathy. With the result being very much the same, we instil value within the struggle and therefore a sense of worth.

Operation: User Recce

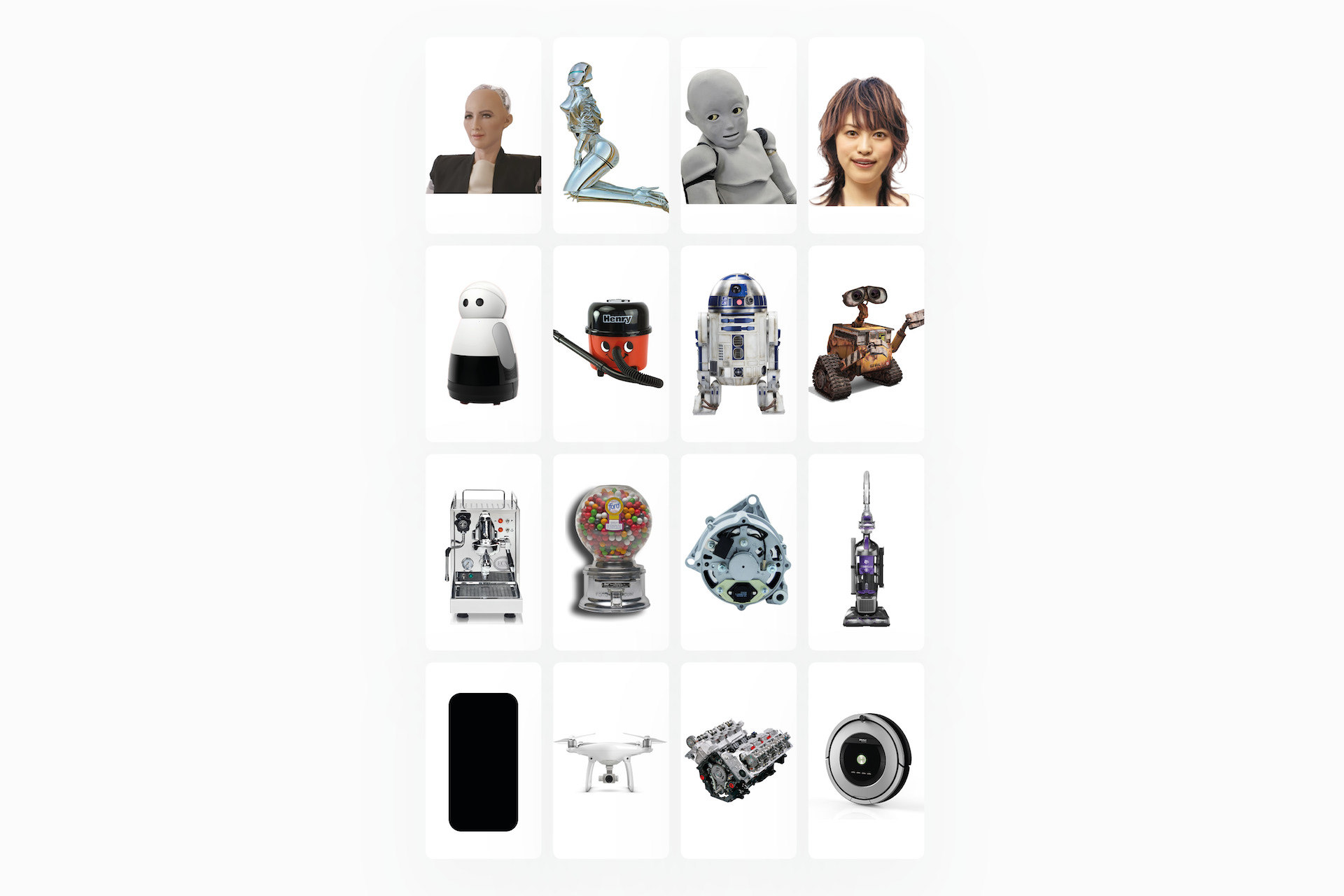

To gain further insights into our questions and queries, we dived into the world of user research. We first created a series of cards, depicting different machines and robots, ranging from abstract metal boxes to almost human-like androids. We also collected several short clips depicting interactions between humans and machines. We showed these to the participants and asked them a range of questions, trying to gauge their opinion on which type of machines and robots were the most pleasing, or least disconcerting, to the participant - in other words, to which equipment they connected the most.

The data pointed to the participants not forming an empathetic connection with a machine that was too robotic whilst feeling a sense of discomfort with anything too human-like. The sweet spot is an object showing human-like behaviour, exaggerating upon our movements and expressions, while looking noticeably different from us.

People are not perfect, therefore neither should our machines be.

Take for example Wall-E - the main character in Pixar’s animation film by the same name. Even though his (and notice that we assign this robot a gender) appearance is very different than that of ours, his actions, movements, and expressions are all exaggerated variations of human behaviour, almost childlike. We trust and like Wall-E and want him to succeed. His defects are charming and add life and character to the machine. People are not perfect, therefore neither should our machines be.

And just like that we leave you with a cliffhanger. We’re equipped and armed now. The rebellion is near.

To be continued…

Greetings from the Stooges:

Jolijn, Rowan, and Will