From Prevention to Resilience

Re-inventing cities with lessons from the pandemic

-

Client:

HvA Civic Interaction Design

- Team:

-

Disciplines:

Concept, UX/UI

-

Schoolyear:

2020-2021

More than a year later, there is still uncertainty on what will be the new normal. The severe restrictions imposed on society forced people into unusual routines and unsought distancing measures. While these measures were supposed to protect humanity from the pandemic, the harms it has caused to people’s wellbeing are only now starting to be noticed, and the toughest realization is how vulnerable we are as a society.

The pandemic forced people to get more creative on how they use the outdoor space. And while, to an extent, cities did adapt to a new way of living, citizens still expect more from planners regarding what public spaces can offer. From Prevention to Resilience is a research project by AUAS research group Civic Interaction Design that aims to go beyond the practical prevention approach to explore how Covid-19 interventions can be linked to making neighbourhoods more resilient, both socially and ecologically considering the current opportunity to redesign our cities. We have an opportunity to make our cities more resilient and sustainable from this day forward.

Our role in this project was to provide insights on what citizens need, and how public interventions can fulfill those needs. We chose a research through design method, where we designed multiple prototypes, tested them, and formulated conclusions that can support the wider project that aims to be finished by 2022.

Exploration

We began our project by mapping the changes that the pandemic created in our cities and visualizing how we could intervene to explore the problem space. We hosted more than 3 co-creation sessions, 30+ interviews, a survey with 50+ respondents and explored an average of 100 academic papers and covid design interventions.

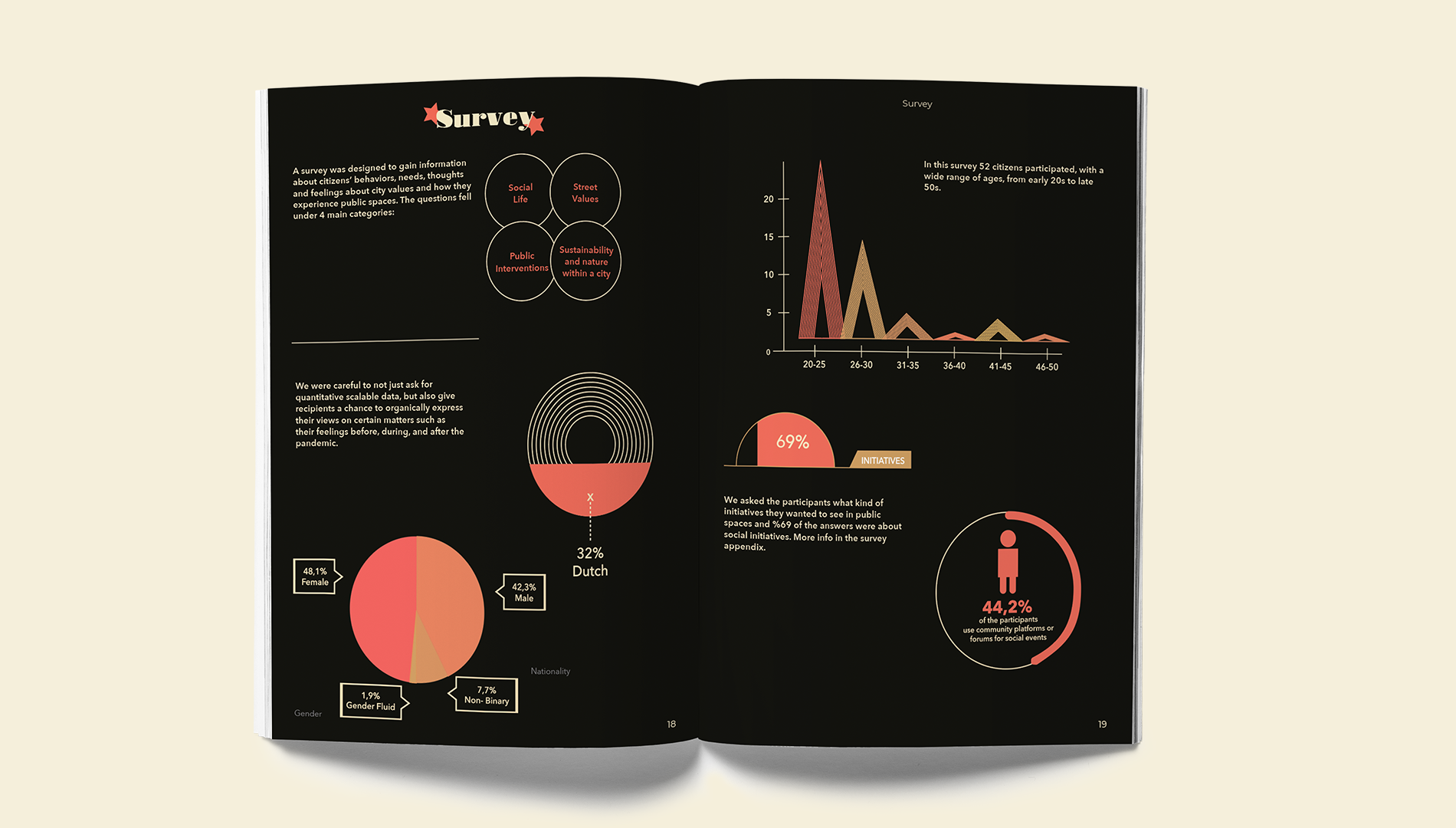

A survey was designed to gain information about citizens’ behaviours, needs, thoughts and feelings about city values and how they experience public spaces. The questions fell under 4 main categories: social life, street values, public interventions, and sustainability and nature within a city. We were careful to not just ask for quantitative scalable data, but also give recipients a chance to organically express their views on certain matters such as their feelings before, during, and after the pandemic.

The main insights from our survey are:

- 69% desire to have more social activities in public spaces

- 64% were open to be in platforms to connect with people of their neighbourhood

- 80% stated that they were lacking civic engagement

- None of the participants suggested ecological or sustainable interventions for their neighbourhoods

- The keywords that were repeated the most in this exercise were ‘lack of spontaneity’

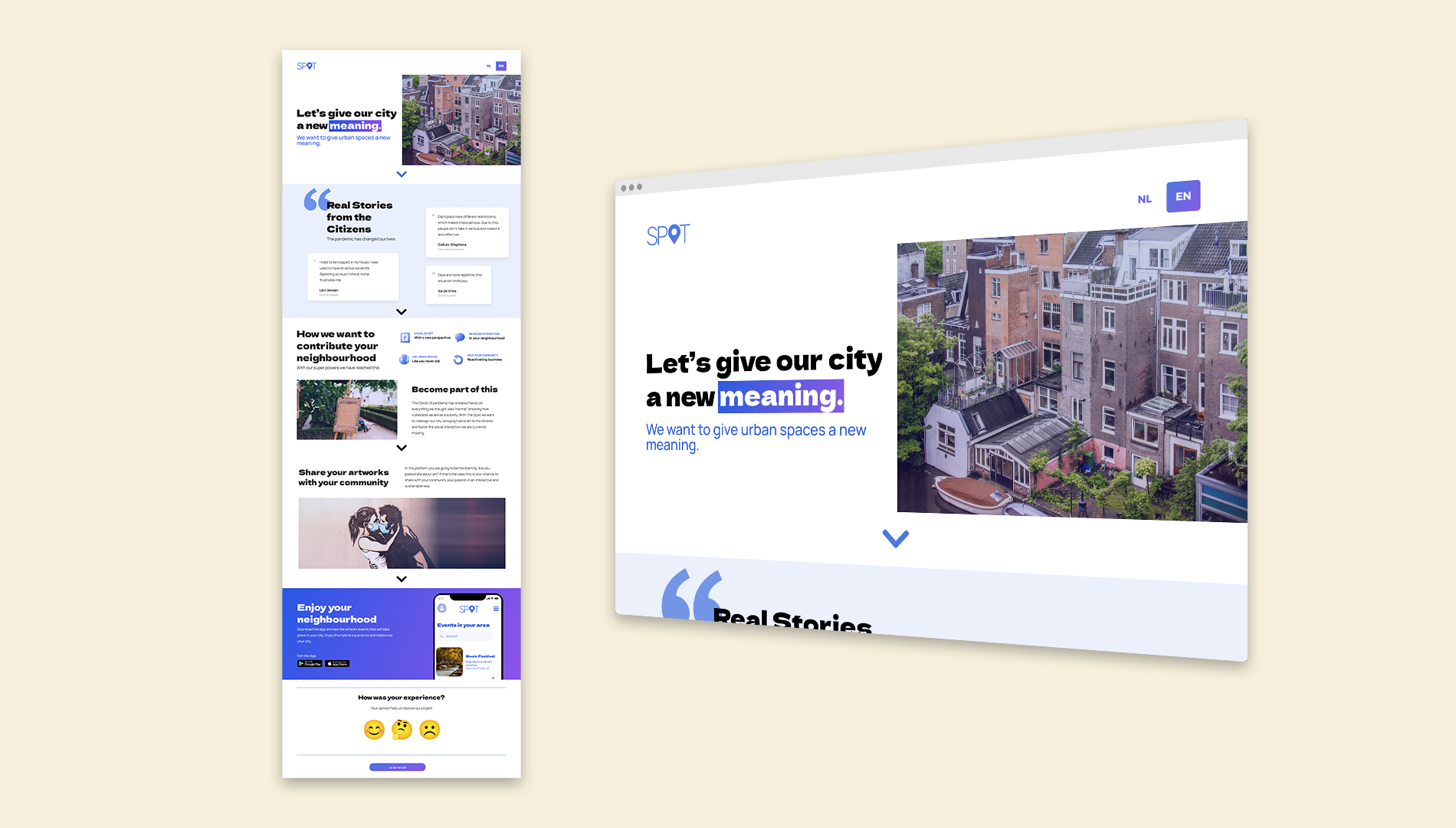

We created a digital community platform, and after testing it with 10 people, we realized we needed to iterate because of its lack of spontaneity.

Additionally, we needed a physical tool. The increase of digitalization led individuals into a societal divide, which, in its turn,led to drastic disengagement and a communal collapse in urban spaces which are losing their social form. Virtual is no longer enough; citizens need to satisfy the mutual social craving. Through spontaneous civic interactions, we can decrease isolation because it decreases the threat of not belonging; a threat that affects physical and mental health.

“Belonging anchors our sense of place in the universe.” - The Ludic City

How can we connect people by repurposing urban spaces for civic interactions?

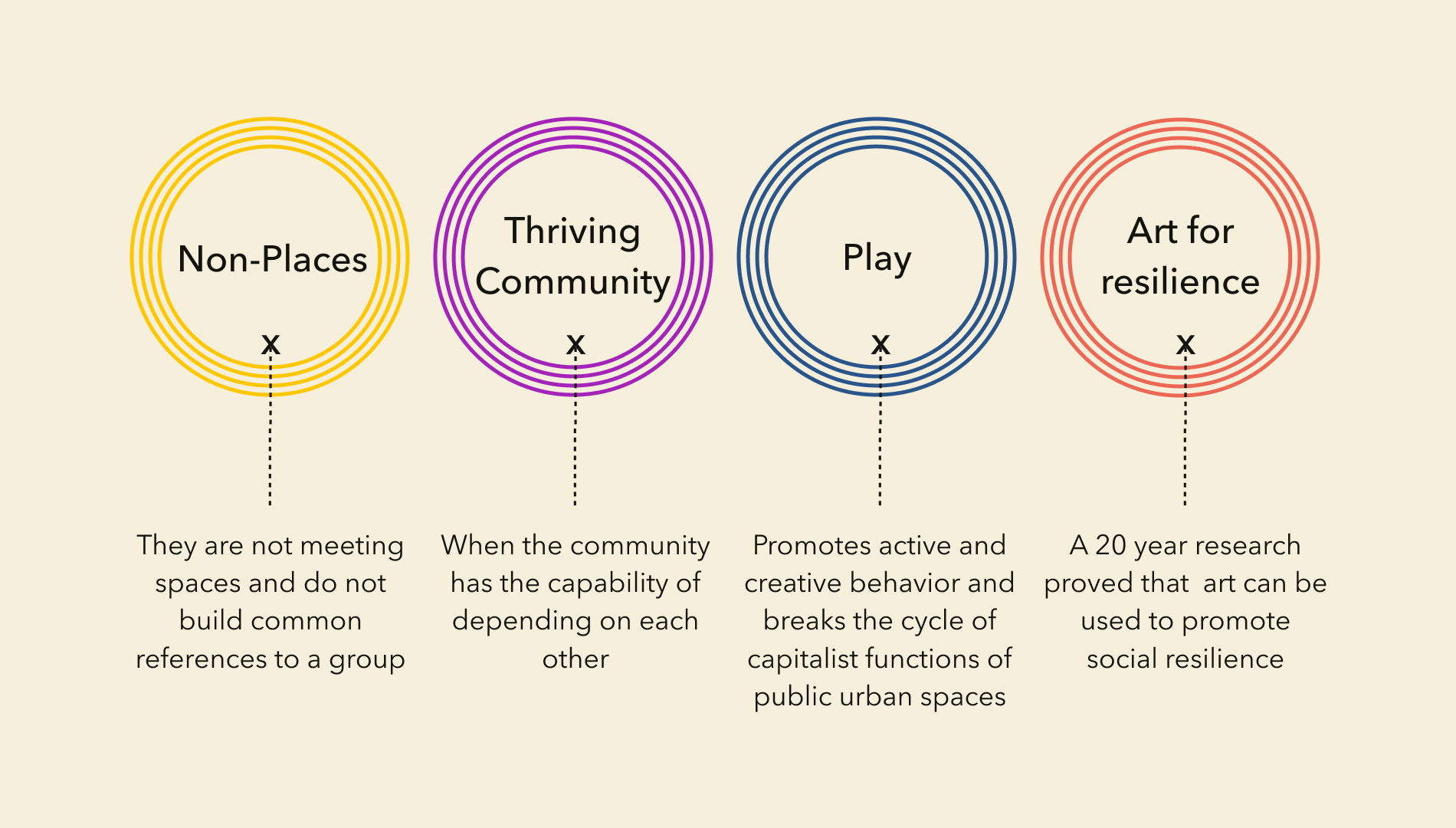

Non-places are spaces that aren’t common or specific, such as the space between a bench and a tree, or a spot on a sidewalk. Non-places can be repurposed to introduce play, which promotes active and creative behaviour and “breaks the cycle of capitalist functions of public urban spaces. It emphasizes the notion that not everything in urban environments needs to be foreseen and functional, but can be spontaneous and simple; free from purpose.” (in The Ludic City)

To design testing tools, we looked at Mccalen’s 3 human motivations to enable us to create a playful intervention:

• Achievement: collaborating and building upon someone’s contribution

• Affiliation: an increased sense of belonging

• Power: status and recognition

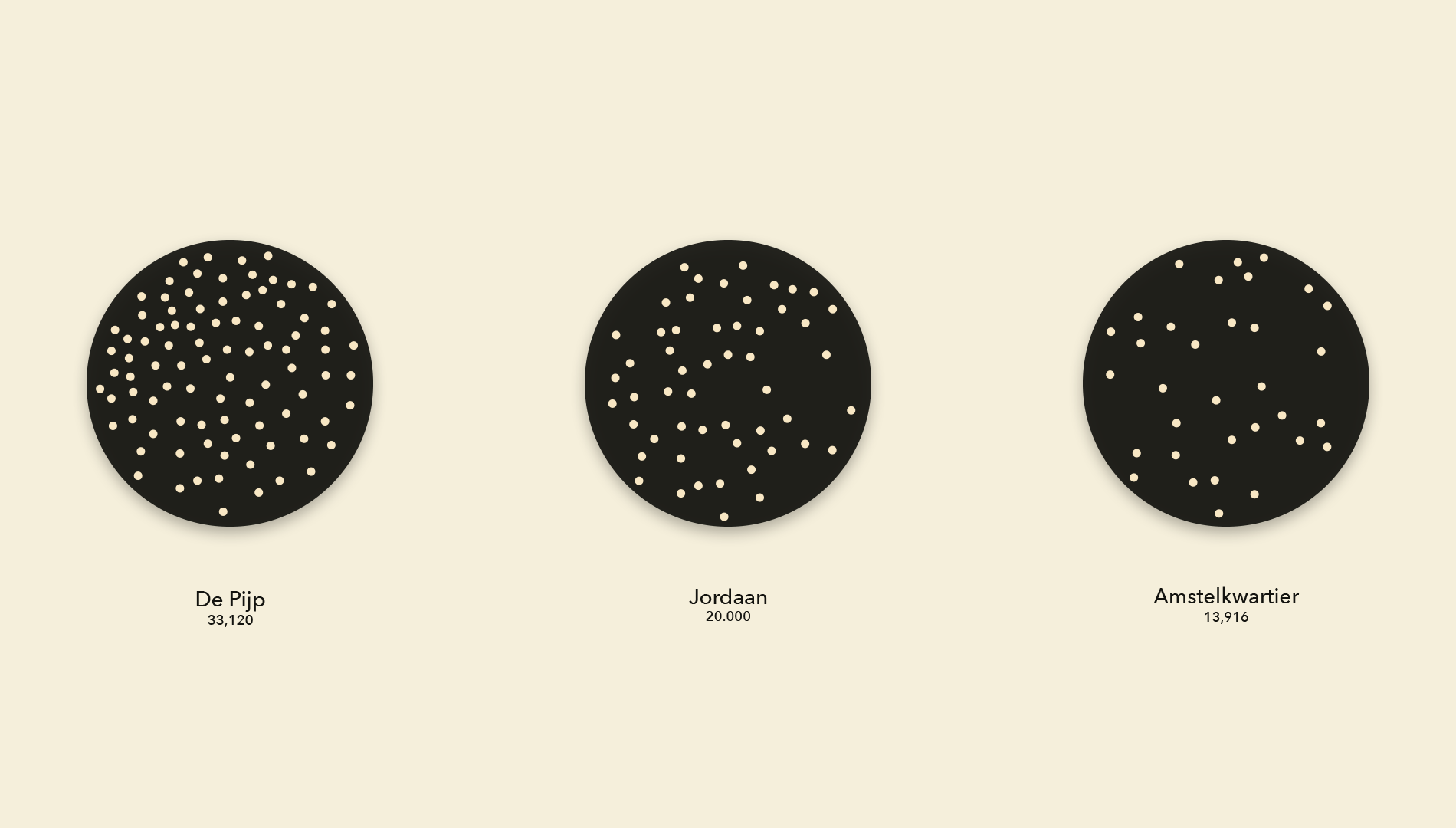

We chose the Amsterdam neighbourhood Amstelkwartier as a testing site. This area has many non-places that can be repurposed with design interventions to make them more resilient. Furthermore, this neighbourhood was ideal due to the small volume of floating population (a group of people who frequently move from place to place), and we wanted to test mainly with residents.

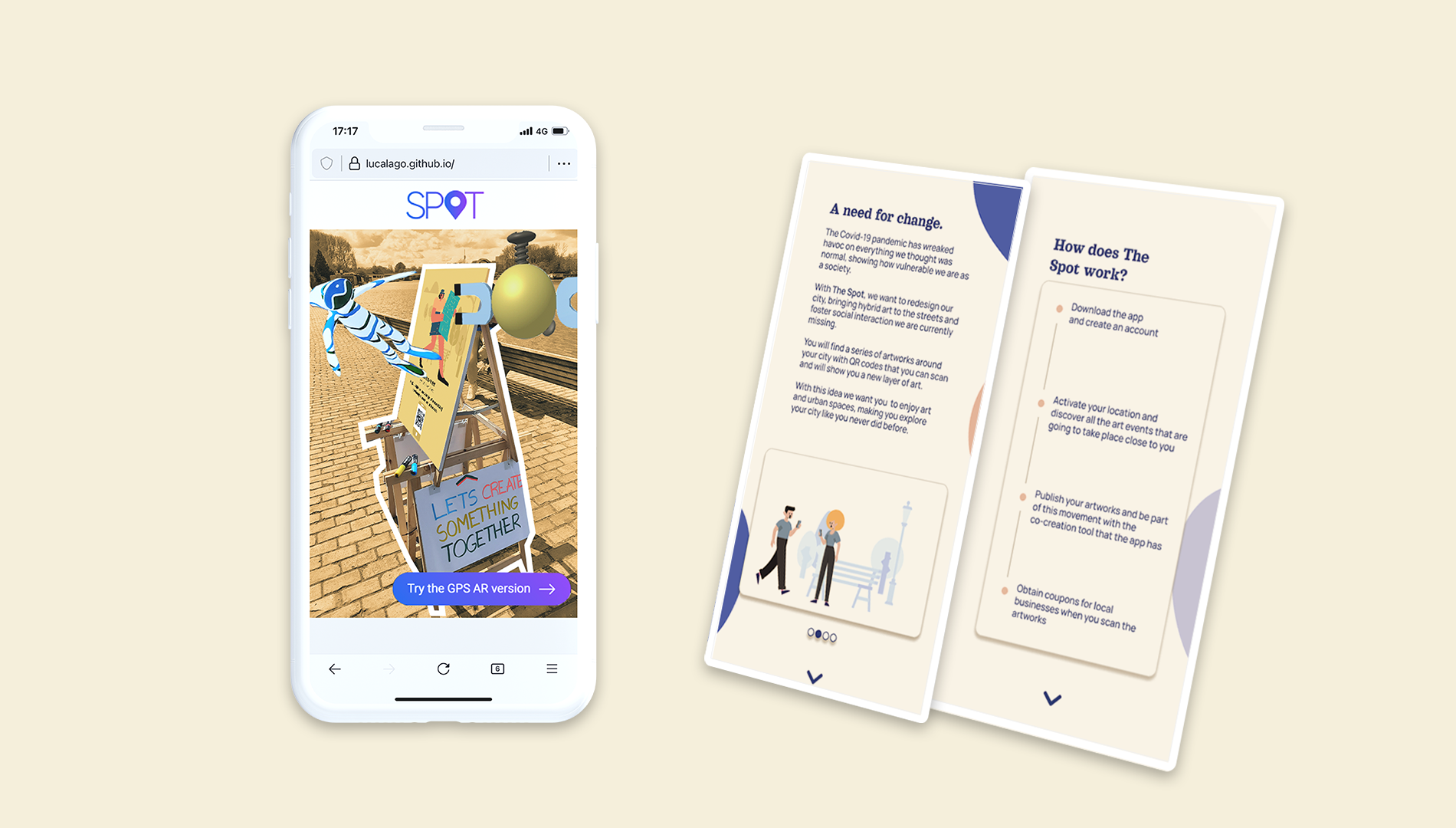

We designed three supporting design testing tools to help us gather and analyse data that enabled us us to learn more about how the citizens of Amsterdam react and behave with repurposed non-spaces. The first play tool was a concept of an open city museum with AR experiences, where people could explore a new layer of their neighbourhoods and collaborate and create art together. Although people liked the idea and style,it wasn't clear how it all linked together and how it could solve the problem of public social interaction.

Additionally, using AR technology meant only targetting a specific niche and we wanted to simplify it to include a majority of citizens. Our user testing proved this wasn’t what people needed in times lacking tactile connectedness.

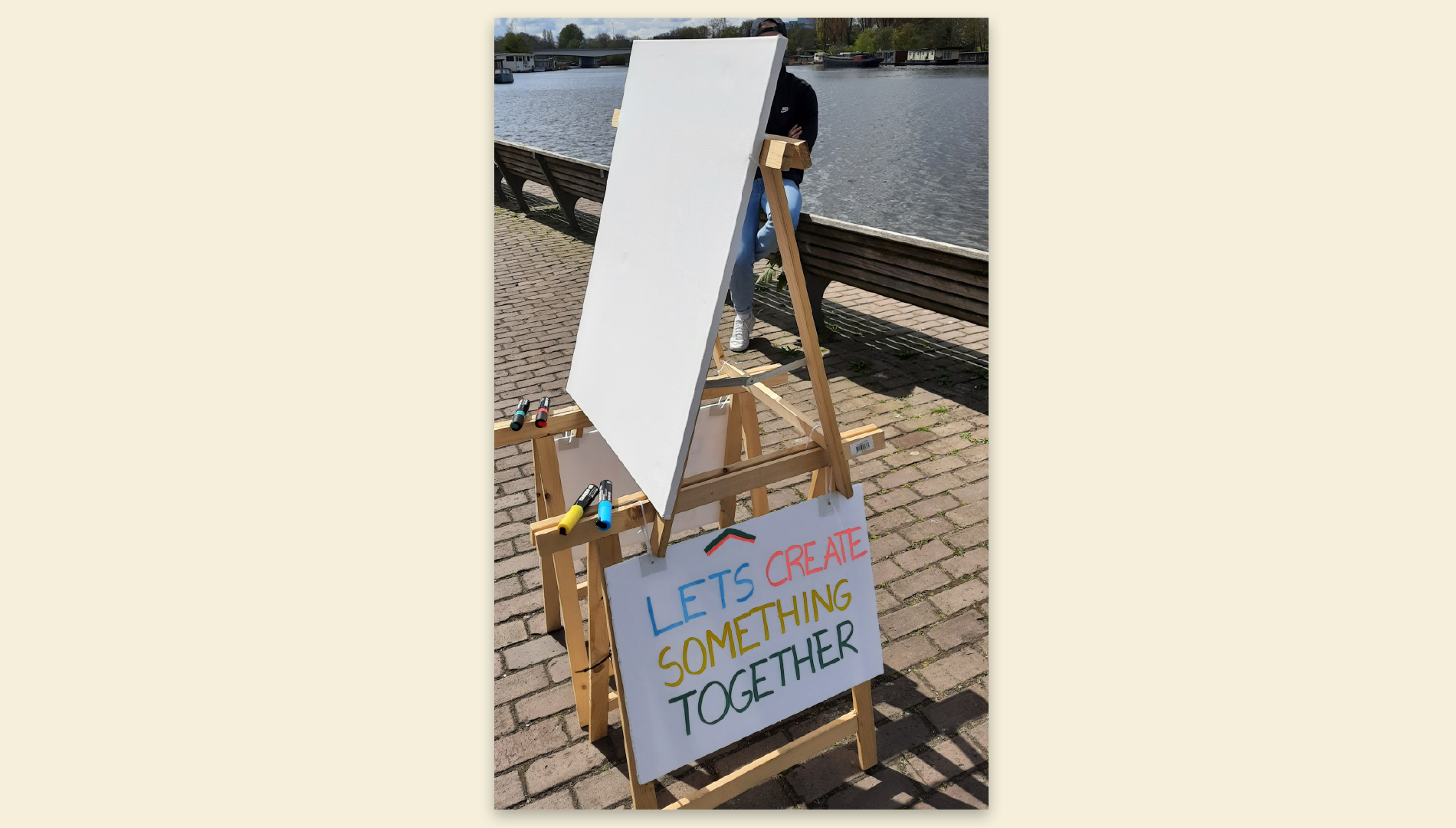

After failing to impress with our phygital approach, we went back to basics: we took a blank canvas out to the Amstelkwartier to observe citizens’ response. We hosted many experiments in different times of the day and in different atmospheric conditions.

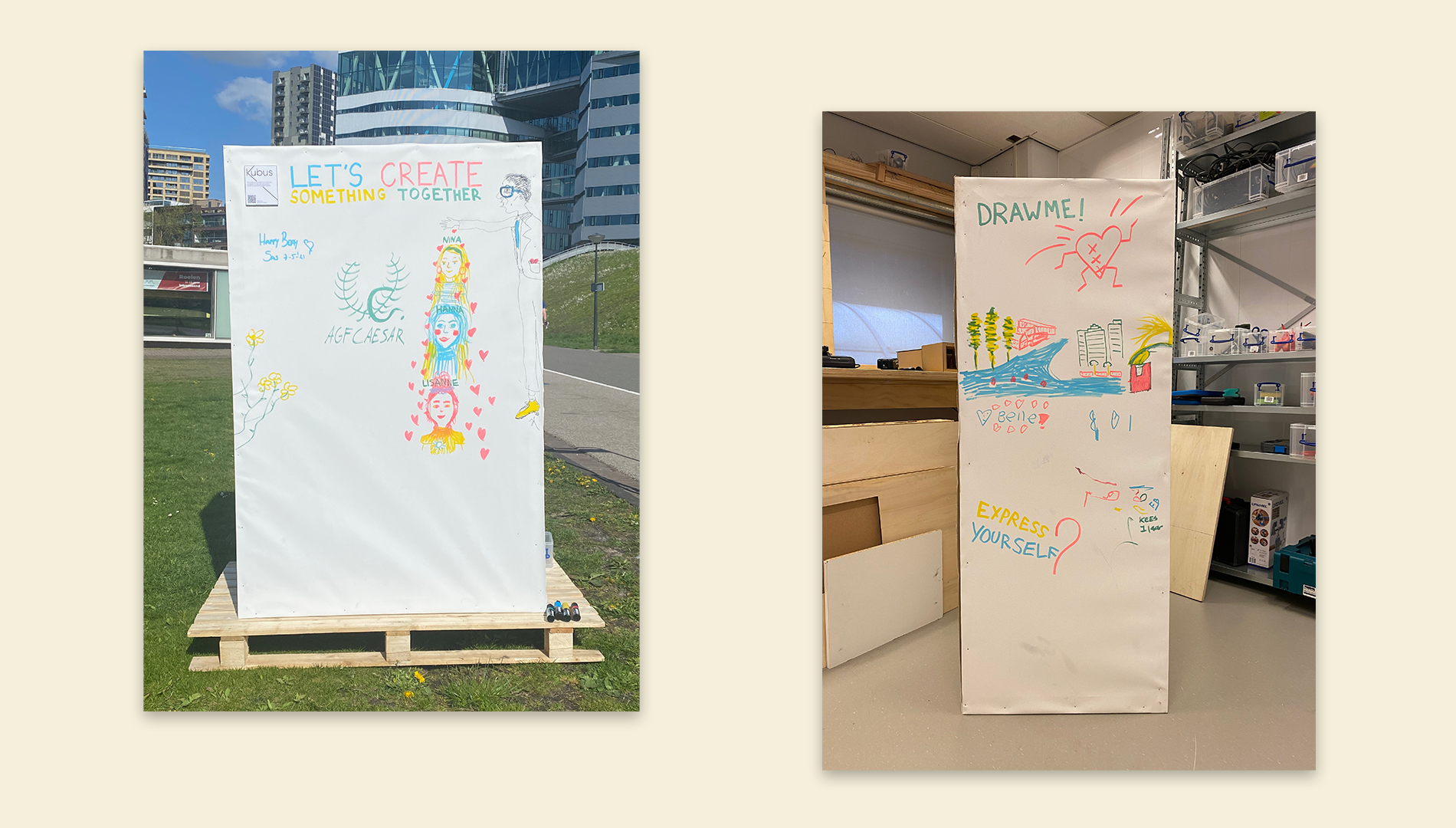

In the nine tests we did, on average of 60% passersby (adults and children) approached, drew on the canvas, and had a positive experience, a “momentarily relief in a busy day,” as one user described it. We also spoke to those who didn’t approach and concluded that there’s a portion of society who is introverted, shy, or when they approached there were already many other residents interacting. 38% of the neighbours interviewed mentioned they came back to the same spot to contribute, and the call to action ‘let’s create something together’ contributed to at least one new Amsterdam resident enhancing her sense of belonging and ownership towards her new neighbourhood.

On a second phase, we developped the concept of ‘neighbourhood diary.’ This time the canvas wasn’t blank but had calls to action such as ‘what do you want to see in this space’ and ‘leave a message for the person behind you.’ The idea was to collect data from a different perspective, see how people feel about their communities, and test the difference between free versus guided prompts.

“Cities are built from the stories of the people and things in them. By listening to their tales, we can collectively write stories to come.” - Daily Tours Les Jours

This pandemic caused many to re-think our economy-driven lifestyles and shift focus onto those that provide more room for wellbeing. Our experiments in the Amstelkwartier provided us with insightful recommendations for city planners and community developers. Our deliverable was a research report with a complete overview on the process and the collective insights, learnings, and conclusions from each phase. It ends with the learnings mentioned above on how designers, researchers and developers can utilize their practice to foster social interaction in public space.

In our report, we provide the 10 crucial learnings what city planners and community developers can do. In short, the learnings are the follwing:

- Break the Rules

- Remember our Five Senses

- Rethink Play

- Time and Place are not Interdependent

- Design for Neighbourhoods

- Foster Nature

- What about Vandalism?

You can learn more in our report, and also find recommendations tailored to different practices.

Our main take away from this project was that in a society where "I" is typically the norm, our experimentation on collaboration showed that, due to the pandemic, there is a growing space for exploring interactions that are about the ‘We’, and this is something that we need to keep investigating.

Check out the video to learn more about this project